In May 2020 I described in my MWO Blog how I’d started work creating a new arrangement of Janacek’s stirring masterpiece The Cunning Little Vixen. I’d opened up my laptop, launched ‘Sibelius’ and hit ‘new’. I then described how Vixen was missing one seemingly important ingredient from the entire score: key signatures! Janacek didn’t bother with them, and that’s okay, I thought; Janacek’s a genius, that’s the way he works, the piece certainly works, and so we simply crack on without key signatures.

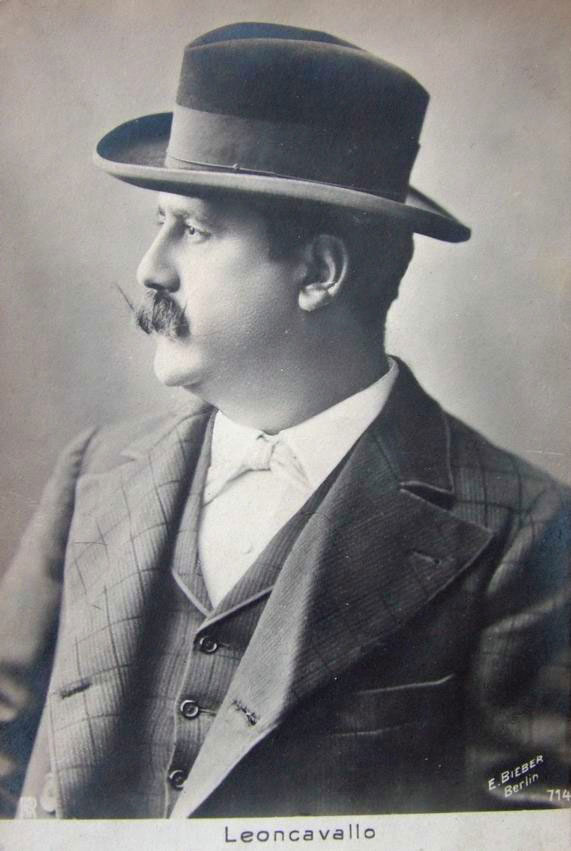

Well, in January this year, I lifted the lid of my laptop, opened up ‘Sibelius’, hit ‘new’ and, with a full score of Pagliacci next to me on the desk, started work on a chamber reduction for five players. I can happily report that everything about the score seemed to be in order, with key signatures present as per normal. Over the course of a few days, however, I began to realise that the composer Leoncavallo appeared to have a somewhat haphazard regard for two other things that music students have always thought of as pretty basic: phrasing and dynamics!

Born in Naples in 1857, Ruggero (or Ruggiero) Leoncavallo began his musical education at the local Conservatory, studying piano and composition. He later took up literature at the University of Bologna for one year, breaking off without obtaining a degree. At around the same time he wrote the music and libretto for his first opera, Chatterton (not performed until much later). A year or so later he headed to Cairo to become a private musician for the ruling family but had to flee in 1882 during the Egyptian uprising, arriving first in Marseilles and then traveling to Paris where he led a Bohemian life, teaching and playing the piano in cafés and restaurants. Haphazard in life as well as in music!?

In 1889 he became briefly involved with the creation of Puccini’s first major success, Manon Lescaut. At this time, Leoncavallo was still undecided as to whether to pursue a career as a composer or dramatist. Puccini’s publisher, Ricordi, thought of him as the latter and commissioned a libretto from him, for Manon Lescaut, which Puccini subsequently rejected (the final libretto is the work of about five different librettists including Leoncavallo).

Leoncavallo and Puccini were about the same age and might have been friends but ended up as adversaries. In 1892 Leoncavallo started working on a version of Henri Murger’s Scènes de la vie de Bohème. At the same time, Puccini also began work on La Bohème. There was fierce controversy, with Leoncavallo now working for the Sonzogno Publishing House in competition with Puccini who was still at Ricordi. Puccini’s opera was premiered in 1896 and Leoncavallo’s in 1897. Both operas were successful, though it was Puccini’s opera that stood the test of time. In a letter to Camille Bellaigue (one of Verdi’s early biographers), Puccini subsequently referred to Leoncavallo’s earlier opera Pagliacci as ‘that vile spectacle’. No love lost there then!

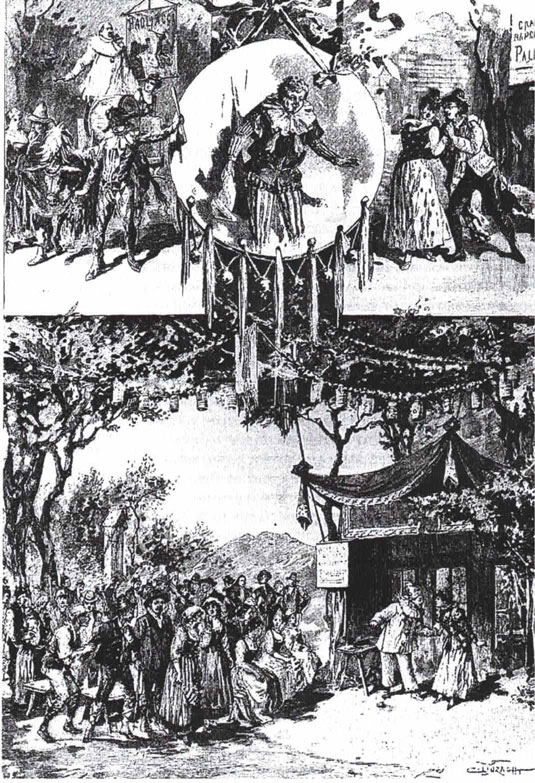

The composition of Pagliacci had taken its cue from another short opera that had appeared in 1890, Cavalleria Rusticana, by Pietro Mascagni. Cavalleria marked the beginning of the operatic genre known as ‘verismo’ and was hugely successful. Leoncavallo was quick to understand its popularity, the nub of which was its social realism combined with good entertainment value. He longed to emulate Mascagni’s success and took his proposed Pagliacci project to the publisher Sonzogno. It was Sonzogno who had published Cavalleria Rusticana after it had been rejected by Ricordi, a huge commercial error as it turned out. Now Sonzogno would have Cavalleria Rusticana AND Pagliacci and make a fortune out of both!

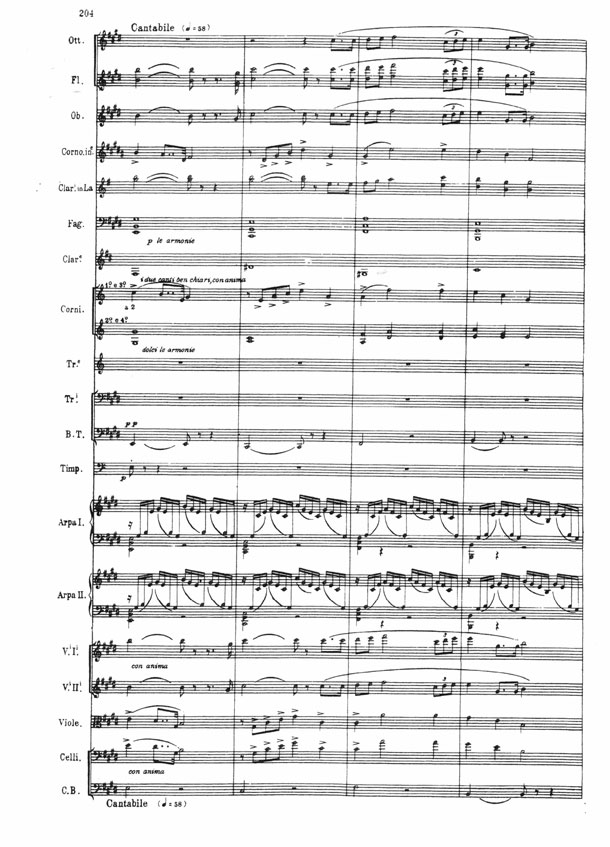

The one thing that surprises me, though, is that Sonzogno never asked Leoncavallo for a few more dynamics, which are sporadic at best. Sometimes the composer adds helpful instructions, such as ‘ruvido’ (rough), ‘affannoso’ (breathless), ‘carezzevole’ (caressing) and, my particular favourite, ‘come un fremito’ (like a shudder). Puccini also uses such adjectives and yet his scores are packed with dynamics; open a page at random from Pagliacci and one from any Puccini score and the difference is clear, with Puccini’s dynamics given far greater micro-management. Similarly, with the phrasing, Leoncavallo is happy to give the strings long sweeping lines followed at times by nothing at all, indicating a general feeling of the music without the nitty gritty of specific bowings that Puccini would normally include. None of this takes away from the genius of the score, but it is unusual and requires quite a bit of sorting out…

The new opera’s success was helped by the casting of the international French baritone Victor Maurel in the role of Tonio. In fact, Pagliacci’s prologue was added especially for Maurel, who felt that his role wasn’t substantial enough. It is Tonio, in the prologue, who sets up the ambivalence between real life and the stage, announcing the opera’s intentions and thereby anticipating the subsequent break-up in theatrical illusion. The prologue, even if it was an after-thought, is an inspired addition to the opera, and most baritones in performance enjoy themselves no end, adding their own high G to the final phrase which Leoncavallo sanctioned but deliberately left out of the score.

Cavalleria Rusticana and Pagliacci make a natural pairing, and I saw this double-bill at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in 2022. I was struck by the way in which Cavalleria’s surging drama is set against a religious backdrop of beautiful choral and orchestral music, whilst Pagliacci’s action sees Canio’s transformation from calmness to violence set against an ongoing blurring of story-telling and reality. The baritone singing the role of Tonio may have added a G in the prologue, but the tenor superstar Roberto Alagna, who had been called in at short notice to replace an indisposed Canio, took it to the next level. The 59-year-old not only delivered the role in spades, but also executed a fine, centre-staged cartwheel to boot! I’ve always had an affection for Cavalleria Rusticana, not least because this was the name my brother gave my first car (yes, it was a knackered old Vauxhall). But, having seen both works paired at the ROH, I think Pagliacci is more ‘fun’!

Jonathan Lyness