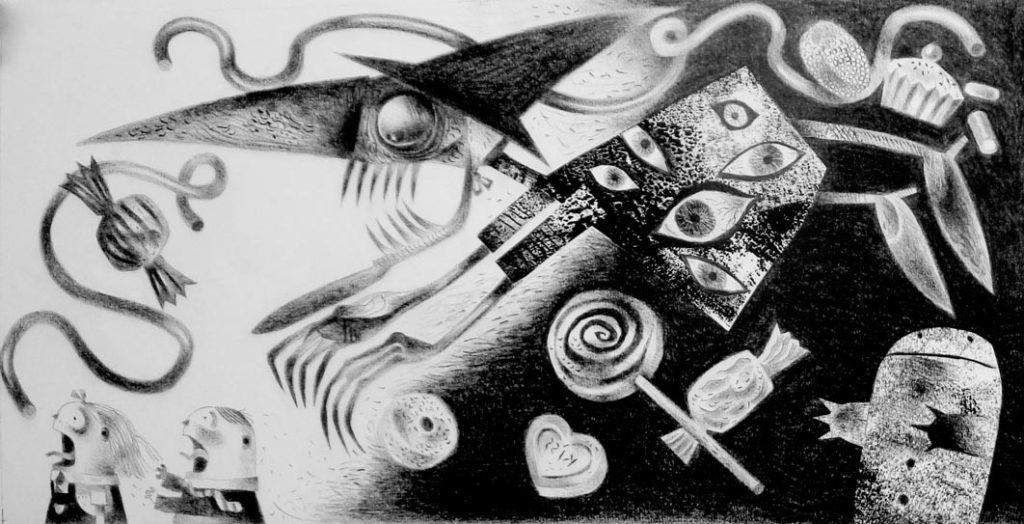

Credit: Banner artwork by Clive Hicks-Jenkins

Fairy Tales are nightmare, not dreamscapes. They play on our primitive and primordial fears. They are the knock in the dark, the crack of a branch, the footstep on the stair rousing you from your slumber.

They are our first moral compass and a navigational tool to steer us through childhood, to warn of the consequences of erring in our youthful ways. Stray from the path and punishment is swift. Trespass upon the forbidden bridge, leave the yellow bricks, taste forbidden fruit and you damn yourself forever more, for the wolf (or the troll) will surely get you. In a world of princesses and dragons, witches and godmothers, Death is Grimm, rarely humane and usually extraordinarily elaborate…

They are our first moral compass and a navigational tool to steer us through childhood, to warn of the consequences of erring in our youthful ways. Stray from the path and punishment is swift. Trespass upon the forbidden bridge, leave the yellow bricks, taste forbidden fruit and you damn yourself forever more, for the wolf (or the troll) will surely get you. In a world of princesses and dragons, witches and godmothers, Death is Grimm, rarely humane and usually extraordinarily elaborate…

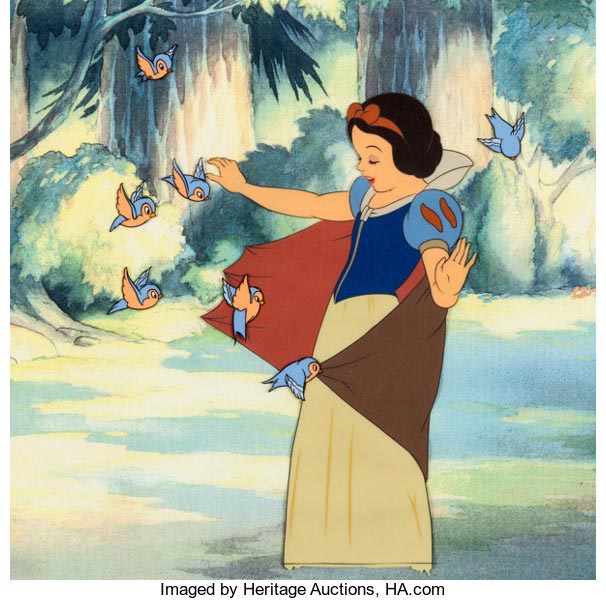

Disney has a lot to answer for in sanitising the genre – rendering horror in glorious animated technicolour where everything is candy-coloured and sprinkled with rainbow sparkling unicorn faeces. In the studio’s world of sugar and spice and all things nice malevolence has been airbrushed. We must not talk too much of horrors that await in the woods. Instead we must sing out with joy and unbridled virginal happiness – “Sing children”, “Sing!” with the beauty and force of Elsa on a sugar rush, “Sing” till the birds of the sky, with artful weave and weft, thread you a dress. “Sing” till your Prince has come…Thank God this diabetes-inducing parade of frippery didn’t exist in the 1890s, for Humperdink’s opera would I fear be a very different show…

Disney has a lot to answer for in sanitising the genre – rendering horror in glorious animated technicolour where everything is candy-coloured and sprinkled with rainbow sparkling unicorn faeces. In the studio’s world of sugar and spice and all things nice malevolence has been airbrushed. We must not talk too much of horrors that await in the woods. Instead we must sing out with joy and unbridled virginal happiness – “Sing children”, “Sing!” with the beauty and force of Elsa on a sugar rush, “Sing” till the birds of the sky, with artful weave and weft, thread you a dress. “Sing” till your Prince has come…Thank God this diabetes-inducing parade of frippery didn’t exist in the 1890s, for Humperdink’s opera would I fear be a very different show…

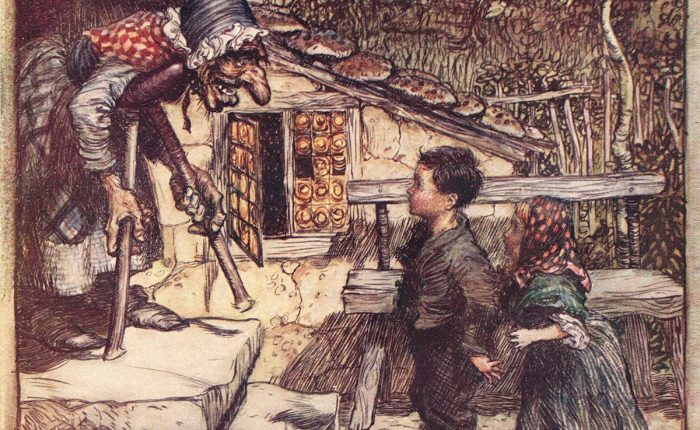

Humperdink’s version is faithful to the story’s dark undercurrents. This Grimm tale plays with ballistic accuracy on the base creatures that it is entrapping in its narrative, both children and adults. The mother who, for a fleeting second turns her gaze and loses a child in the supermarket, shares the same visceral fear as Hansel’s Dad and Mum as they realize their golden twins are lost to the woods.

What loving parent has not, in a moment of frustration, banished their child from their presence – prematurely and temporarily untethering the apron strings. Hansel and Gretel’s parents love them, but their situation is cruel and in the midst of grinding poverty, with the challenges of father’s unemployment and mother’s sense of inadequacy, who wouldn’t cry over spilt milk and scream at the kids? That Humperdinck makes much of the poverty the household faces allows us to show compassion to the parents when, at face value, we could easily judge them with contempt in the opening scenes.

The horror in Hansel and Gretel emerges from the familiar. The children in their naivety are so transfixed by the culinary delights they fail to recognise stranger danger. This vulnerability of the child is borne of an unswerving belief in the infallibility of the adult. Hansel and Gretel are not the first to fall for the benign little old lady routine. Much as little Red Riding Hood fails to connect grandma’s ferociously oversized teeth with her impending role at the wolf’s ‘dinner for two’, Hansel and Gretel forget to question the motive of this unlikely confectioner. As the story unfolds, we are left hiding behind the sofa screaming ‘don’t go through the door’, as if watching a teen flick horror movie.

The horror in Hansel and Gretel emerges from the familiar. The children in their naivety are so transfixed by the culinary delights they fail to recognise stranger danger. This vulnerability of the child is borne of an unswerving belief in the infallibility of the adult. Hansel and Gretel are not the first to fall for the benign little old lady routine. Much as little Red Riding Hood fails to connect grandma’s ferociously oversized teeth with her impending role at the wolf’s ‘dinner for two’, Hansel and Gretel forget to question the motive of this unlikely confectioner. As the story unfolds, we are left hiding behind the sofa screaming ‘don’t go through the door’, as if watching a teen flick horror movie.

In the land of make believe, as much as it is in reality, nothing is quite what it seems. Who hasn’t fallen for evil’s ‘masquerade’ – the depravity normality masks? When as children we watched Jim ‘fix it’ how were we to know? When as children we watched Maggie clasp her flasks of beetroot juice to her breast, to demonstrate with kitchen science a rudimentary litmus test – how were we to know? There on TV in Mum’s front room, a whopping 14 inches of black and white, she charmed and bewitched in the name of education and science to entice the children. How were we to know that ‘neath golden mane, ‘pon the good ship ‘Blue Peter’, the ‘Milk Snatcher’ lay in wait…