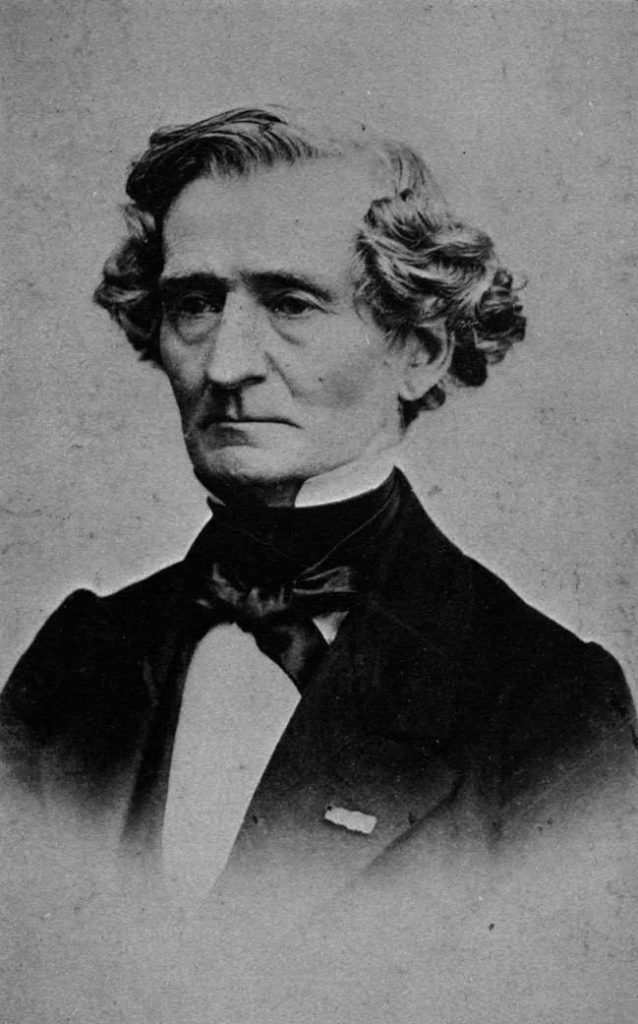

I have to be honest: I’ve always had a somewhat equivocal relationship with Berlioz. And I know that, amongst musicians and music lovers, I’m not alone. Some of his works have widespread appeal, such as the song cycle Les nuits d’été and the celebrated Symphonie fantastique. And I’ve always adored the love scene from Roméo et Juliette since studying it as a student. After that, when I ask around (and I’ve asked around quite a bit since planning Béatrice et Bénédict with MWO), I get a slightly questioning, even bemused response. It seems to me that people just don’t know what to make of him!

Listening to the Symphonie fantastique, it is almost unbelievable that it was premiered just four years after Beethoven’s ninth. But Berlioz (1803 – 1869) didn’t belong to the dominant German or Italian traditions. He belonged to the French tradition, and much of that tradition is missing from today’s world. We hear the music of earlier French composers such as Lully and Rameau, and also Gluck whose European credentials include enough music written for France to give the French good reason to have adopted him.

None of these, however, prepare us for Berlioz. The music of his immediate predecessors – Spontini and Cherubini (both Italian by birth but working and living in France), Étienne Méhul, François-Adrien Boieldieu, Nicolas Dalayrac etc. – is virtually unknown. So Berlioz’s music appears to have come out of nowhere – for most of us he is the first of the French composers. Added to that, he was one of music’s great experimenters and innovators. Not surprising, then, that if one compares Berlioz to other more familiar early romantic composers – Schumann, Mendelssohn or Chopin – it may feel at times as if Berlioz’s music was put together in a science lab.

But his final composition Beatrice and Benedict doesn’t come across as the least bit experimental. On the contrary, first impressions are of a score that is simple and subtle, radiant with charm, wit, love and exuberance. Its polish and execution in every detail proclaim a composer with a lifetime’s experience. Berlioz himself described it as ‘a caprice written with the point of a needle’, and the composer’s inimitable harmonic twists and turns persist throughout the piece. So too does his breathless energy, contrasting with his penchant for space and breadth; if ever there was a composer who wrote music that was either fast or slow, Berlioz is that composer.

But his final composition Beatrice and Benedict doesn’t come across as the least bit experimental. On the contrary, first impressions are of a score that is simple and subtle, radiant with charm, wit, love and exuberance. Its polish and execution in every detail proclaim a composer with a lifetime’s experience. Berlioz himself described it as ‘a caprice written with the point of a needle’, and the composer’s inimitable harmonic twists and turns persist throughout the piece. So too does his breathless energy, contrasting with his penchant for space and breadth; if ever there was a composer who wrote music that was either fast or slow, Berlioz is that composer.

MWO started thinking about a Shakespeare season a few years ago. We wanted to stage one of the great Verdi/Shakespeare operas as MWO’s MainStages spring production. This left us with a quandary as to what to do for our SmallStages tour. Thinking about Verdi and his passion for Shakespeare led me to think about Berlioz and his similar passion for Shakespeare. They are the two great Shakespearean composers of the c19th, arguably of all time. Remarkably, just as Verdi turned to writing a Shakespearean comedy at the end of his life, so too had Berlioz. And just as Falstaff confirmed Verdi to be at the height of his powers, so Beatrice and Benedict had confirmed Berlioz’s inspiration to be in full flight.

It was 1860 and Berlioz had been thinking about Much Ado About Nothing for over 25 years. That year he wrote a libretto of his own, focussing on the lead characters Beatrice and Benedict to create a one-act opéra-comique, a genre of French opera with musical numbers separated by dialogue, the most famous example being Bizet’s Carmen composed around a decade later. He wrote most of the music that autumn, starting with nine musical numbers. This he subsequently increased to twelve, dividing his opera into two acts, though Act 2 was a bit short. And so he expanded Act 2 with a trio and a chorus. Within the opera he inserted a curious instrumental dance number which he borrowed from previous material – a ‘sicilienne’ – heard early on and again about mid-way through, which Berlioz had written as a teenager some 40 years earlier (back then it was a little romance entitled Le dépit de la bergère).

The opera is scored for a relatively modest orchestra, though there is one chorus requiring two harps, an expensive addition for just one number, though in this regard Berlioz had form – Les nuits d’été requires a harp for just 5 bars! For a drinking song he adds a guitar, a tambourine and Verres frappés sur la table – ‘shot glasses’ to you and me! Most of the parts are highly demanding and the music is unusually distributed. The violas and trumpets play key roles, and his love for the ‘singing’ qualities of the cello is apparent throughout.

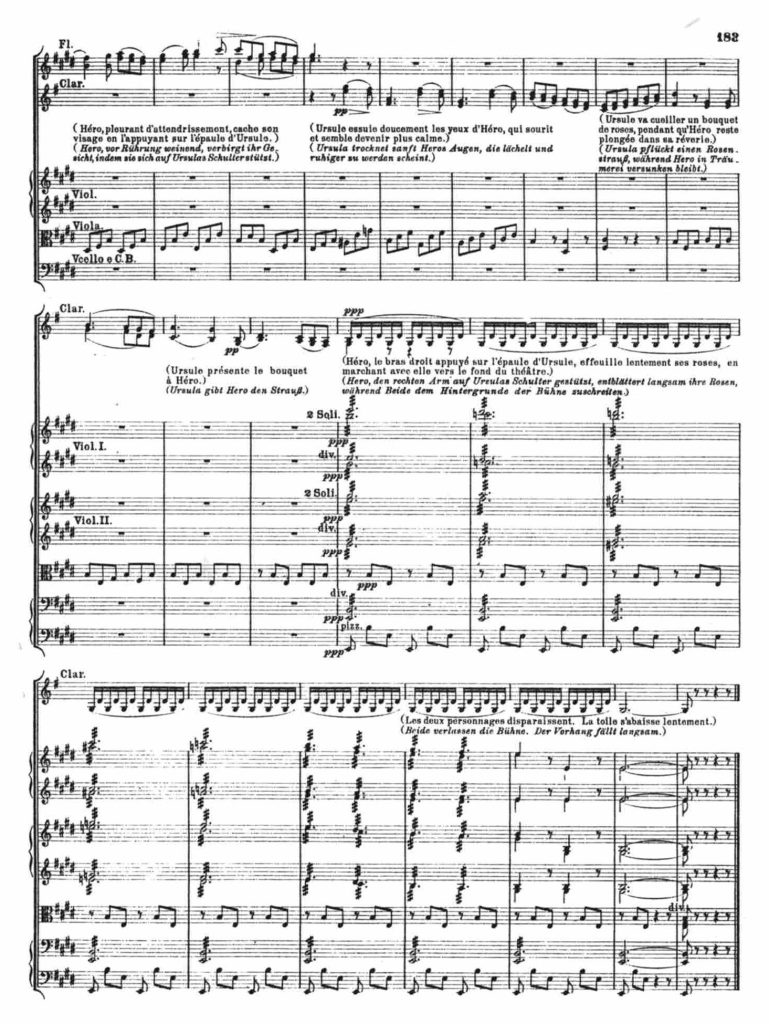

Amongst the wind, the clarinet is particularly prevalent, in all its registers, from high melodies to a most extraordinary passage at the end of the opera’s famous central Duo-Nocturne. Indeed, the ‘play-out’ of this most beautiful of duets contains music the like of which I’ve never come across before. First, there is a slow, lengthy, meandering duet between a pair of flutes, followed by a pair of clarinets, with nothing but a single viola pizzicato line for accompaniment. And then, to finish, Berlioz gives us high, ethereal ‘tremolo’ violins, a low pizzicato double bass, and an extraordinary ostinato clarinet figure that just keeps going and going, at the very lowest part of the instrument.

After which, without a break, Berlioz pitches us into the above-mentioned sicilienne, led by the clarinet which, for seventy bars, has nowhere to breathe (as I write I’m not sure our clarinettist knows this yet!). I’ve had a lot of fun arranging the music for our little band of touring musicians – violin, cello, clarinet and piano. I’ve only just finished it and can’t wait for our audiences to witness and hear this beautiful, energetic, expressive and, at times, exotic little opera. We have no harps for this production, and there’s no guitar either (though the violinist may make you think otherwise). But we do have a tambourine, and we do have shot glasses which no doubt could be made use of before, during and after the show, as required.

Jonathan Lyness