Once upon a time, an author was commissioned to produce a charming tale as a primer book for children to help them to learn to read. He was so frustrated with the list of prescribed words he was allowed to use that, one day, whilst sitting at his desk he resolved to weave a story around the first two words in the list that rhymed. The first two words he came across were Hat and Cat, and in that moment one of the world’s best loved books was born and the author lived very happily ever after.

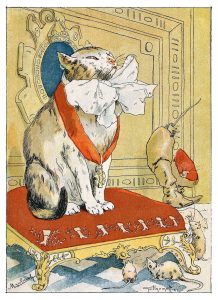

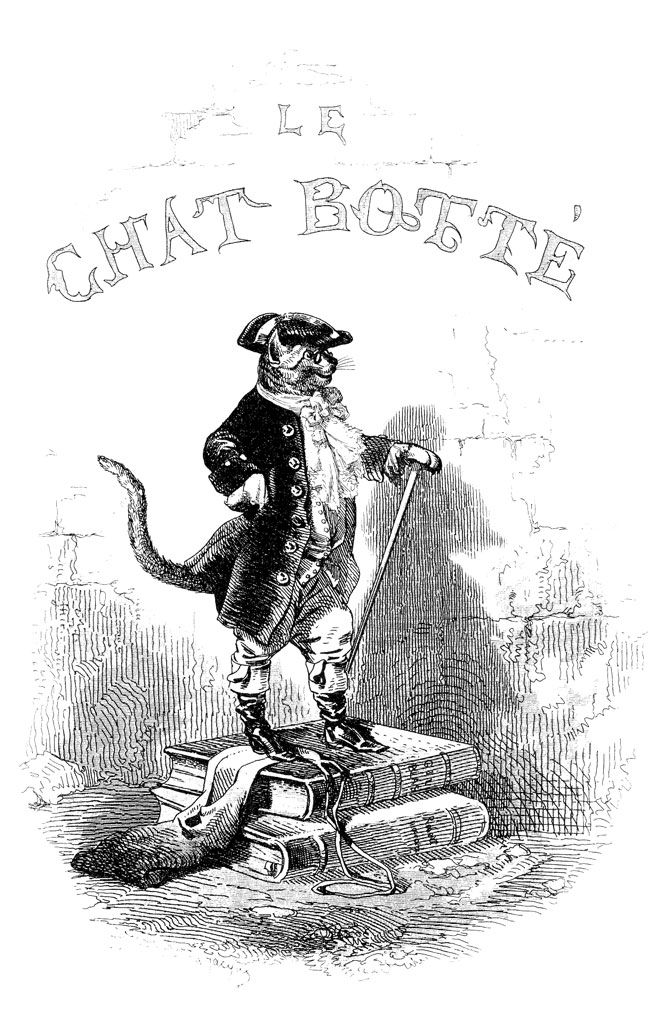

Who doesn’t love an animal in a costume? A cursory search of social media will produce a multitude of images (if you doubt me then google ‘dog, fancy dress costume, for sale’..) and the hero of Montsalvatge’s short one act opera Puss in Boots is one such character – an anthropomorphic cat in a pair of giant boots.

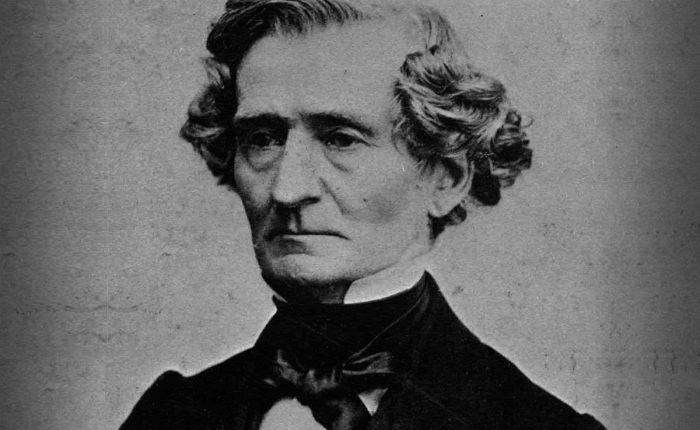

Puss’s narrative is almost as old as the hills. The first known written version of a cat attempting to make their fortune in a King’s palace dates back to the second century BC in the Panchatantra – a collection of Hindu Tales based on older oral traditions. In its modern European form the story can be traced to the publication in around 1550 by the Italian writer Giovanni Straparola. Other authors tackled the tale – Basile in 1634 and a more famous edition in 1697 by Charles Perrault, a member of the Academie Francaise, titled ‘Histoires ou contes du temps passe, avec des moralites’ (Stories from past times with morals). The book was subtitled Mother Goose’s Tales – a more familiar title to many.

The stories in Perrault’s collection are familiar to us all, Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella, Bluebeard et al and to a modern audience the morals of many of them are clear and obvious. Like Dr Seuss’s eponymous narrative the function was to educate children, but not, as with The Cat in a Hat, in literacy but as part of their moral education. What makes Puss in Boots stand out to a modern reader is that in our present society (with the possible exception of the current political machinations) the story seems the very opposite of a good ‘moral’ education. Here we have a character that lies, steals, cheats and indeed is willing to break any contemporary modern moral code to achieve his goal.

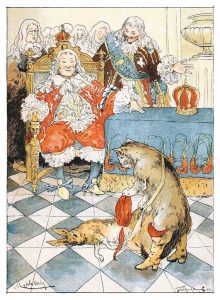

Puss in Boots is an amoral story – but not, as is the case with many fairy stories, a cautionary tale. What Puss offers is the hope that by diligence, hard work and commitment even the weakest can survive, providing you dress well and become ‘acceptable’ to your betters. We cannot not judge Puss in Boots through modern eyes; his story in its current form rose to prominence during the Age of Enlightenment, a time when men’s hard work and talent could indeed elevate them to the highest courts in the land. He may not be much of a tree climber but Puss in Boots proves himself superb at scaling the social ladder. Puss is self-serving, self-aggrandizing and, frankly, a cad. In the folk tradition Puss in Boots falls into the ‘animal as helper’ category but his assistance to the impoverished miller is tainted by his final goal – to secure a life of redolent luxury for himself.

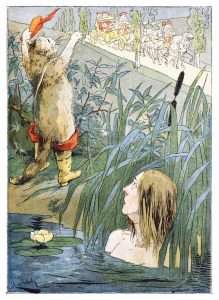

Puss makes much in the story (and indeed in Montsalvatge’s setting) of his need for a fine pair of boots, a cape of red satin, sword, silver buckles and a sombrero with a plume of feathers. In the world of Charles Perrault, these fabulous fashions would have taken on a whole other layer of significance. Perrault was a writer, but also a statesman, and in charge of Louis XIV’s artistic and literary policies as Secretary of the Petite Académie established in 1663. He oversaw building work at the Louvre and Versailles and as a key figure in the ‘Sun King’s’ flamboyant court, Perrault was well aware of the need to dress to impress. His stories were published when he was 69, after his fall from grace within the French court, and their subversive elements – Cinderella the servant girl rising above her upper class siblings, the lowly miller passing himself of as the Marquis de Carabas – doubtless owe a debt to his own observations of the lives of those caught up in the social whirl of palace life where appearances mattered more than social standing. In 1668 King Louis passed an edict that required all his courtiers to remain fashionable, the King himself wore red heels as a symbol of his elevation above the rest of humanity. He also declared that anyone sufficiently well-dressed would be allowed to enter the gardens of Versailles – this truly was a world in which a cat, if correctly dressed in the fashion of the day, could look at a king.

We may laugh at the idea of a cat in an elaborate hat but Puss (and Perrault) know better, for these are the tools by which he’ll secure his elevation to the palace and who knows perhaps even the throne (for an occasional catnap) and a life of ‘happy ever after…’