Our Music Director Jonathan Lyness began his labour of love, creating a new score for four instruments to perform Puccini’s Il tabarro, in November 2019. Now, a year later than expected due to the Covid pandemic, he’s preparing the instrumental parts ready to send to his three fellow musicians and bring the work to life for the first time on our SmallStages tour. In his latest blog Jon introduces us to Il tabarro, and Puccini’s evocative recreation of 1900s Paris by night.

Our Music Director Jonathan Lyness began his labour of love, creating a new score for four instruments to perform Puccini’s Il tabarro, in November 2019. Now, a year later than expected due to the Covid pandemic, he’s preparing the instrumental parts ready to send to his three fellow musicians and bring the work to life for the first time on our SmallStages tour. In his latest blog Jon introduces us to Il tabarro, and Puccini’s evocative recreation of 1900s Paris by night.

Puccini seems to have felt a special affinity with Paris, so much so that MWO, in conceiving its “Puccini in Paris” season, was almost spoilt for choice. However much we think of Puccini as an Italian composer, he most certainly spent his life composing operas set elsewhere. In chronological order, we have Germany, Flanders, France/America, France, Italy, Japan, America, France, France, Italy, Italy and China. Throughout the sequence the Puccini stamp, like that of all great composers, is clearly there, paradoxically so, when one considers how brilliantly he manages to immerse himself within the musical colour of his temporarily adopted geographical location.

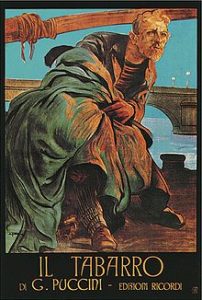

The original idea for Il tabarro had come to Puccini in 1912 when he saw, in Paris, the play La Houppelande (The Cloak) by Didier Gold. Puccini wished from the start to compose three one-act operas to be performed together in one evening but it wasn’t until 1916 when, having completed Il tabarro, he seized on two newly created subjects by the young playwright Giovacchino Forzano: Suor Angelica (set in a convent in Siena) and Gianni Schicchi (set in Florence and based on a few lines from Dante’s Inferno). Puccini worked fast on both his ‘nun opera’, as he called it, and Gianni Schicchi, finishing both by April 1918.

The original idea for Il tabarro had come to Puccini in 1912 when he saw, in Paris, the play La Houppelande (The Cloak) by Didier Gold. Puccini wished from the start to compose three one-act operas to be performed together in one evening but it wasn’t until 1916 when, having completed Il tabarro, he seized on two newly created subjects by the young playwright Giovacchino Forzano: Suor Angelica (set in a convent in Siena) and Gianni Schicchi (set in Florence and based on a few lines from Dante’s Inferno). Puccini worked fast on both his ‘nun opera’, as he called it, and Gianni Schicchi, finishing both by April 1918.

Next, the three operas required an overall title, and various ideas were considered, such as trinomio (trinomial), treppiede (tripod) and triangolo (triangle!). Finally Il trittico (triptych) was chosen, though this is a misnomer. A triptych is usually a single artwork in three sections. Puccini’s three operas were not specifically devised with a common theme, though some have tried to find one, such as the idea that they reflect Dante’s Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso, or that a ‘hidden death’ plot feature links the three. Anyway, Il trittico it was and, because of the war, the premiere took place at The Met in New York. It was December 1918, about a month after Armistice, and with transatlantic travel still dangerous because of mines, the composer was for the first time unable to attend one of his own premieres.

Puccini originally resisted the idea that the operas could be performed separately, but even he acknowledged that Il trittico made for a long evening. I’ve seen Il trittico live on stage, once, at English National Opera, probably about 20 years ago. It is a long evening, but the contrast between each opera actually heightens the dramatic impact each delivers. And there is a natural progression – from the melodrama (or verismo – Italian realism) of Il tabarro, to the spiritual tragedy of Suor Angelica, to the morbid comedy of Gianni Schicchi. Now commonly performed separately (or paired with other one-act operas) all three have their fan-base, and no doubt if MWO were to perform all three together then our audiences could argue amongst themselves as to which is the best!

Il tabarro contains one of Puccini’s most modern and impressionistic scores, with clear influences of Debussy and even Stravinsky. The memorably drifting theme of the opening – the ‘river music’ – with its regular swaying motion, conjures up the sluggish flow of the waters of the Seine, the effort and weariness at the end of a working day, the monotony of life on board the barge and the heat of the Paris evening. The working song of the bargemen breaks things up, rough-hewn in nature (Puccini actually marks ma ruvido – rough, in the score) before the river music returns, as it keeps doing throughout the opera.

However, don’t despair! After this rather bleak introduction, the composer livens things up. First, we get a spirited drinking song from the young Luigi. This is followed by a French waltz from a desperately out-of-tune street organ; Puccini scores this with clarinets and ‘out-of-tune’ flutes, playing not in octaves but in major sevenths. And then a song-seller touts his wares with a short number telling the story of Mimi that includes a clear musical reference to Puccini’s own Mimi from his earlier opera La bohème. Puccini wasn’t the first to reference his own music; Mozart did it in Don Giovanni, and Wagner in Die Meistersinger.

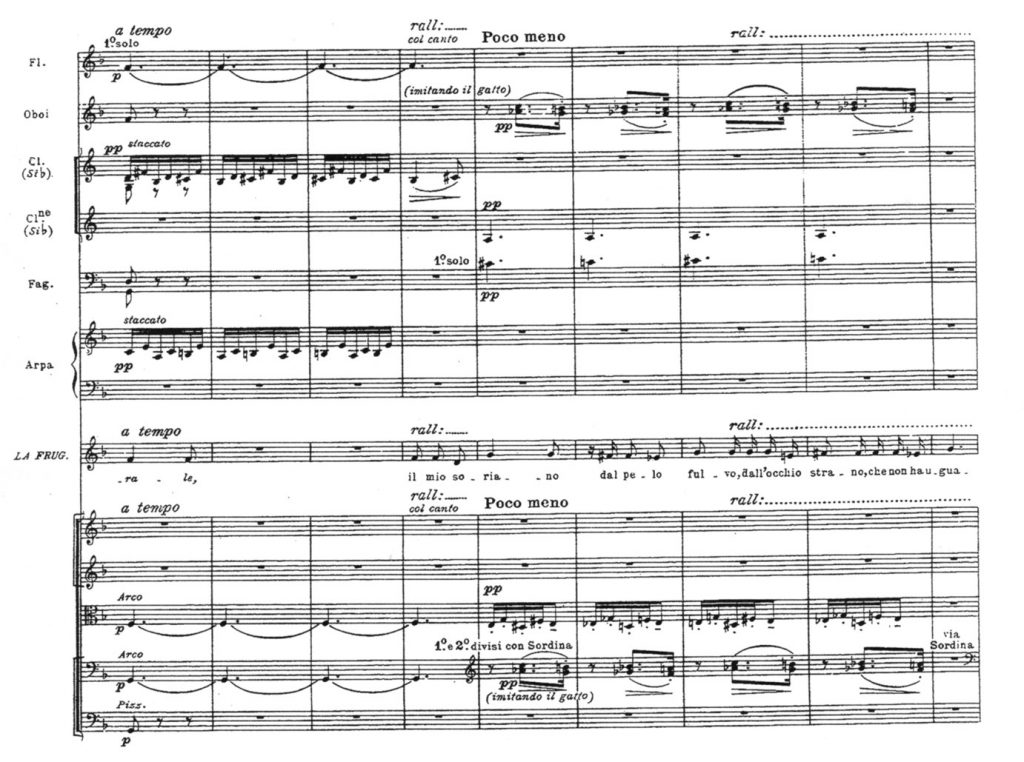

La Frugola, the ‘rag-picker’, makes her entrance, hobbling along with a sack full of old stuff, arriving to collect her husband Talpa. She gets two songs, both primitive and somewhat unreal, the first of which includes endless pizzicato, raucous bass notes with gruff-sounding grace notes and a passage where the musicians are given the instruction imitando il gatto – sound like a cat, which of course everyone learns to do early on in their training! La Frugola’s second song is no less surreal – based on a phrase in which one note is repeated many times over.

When La Frugola finally leaves the stage we are left with our three main protagonists – Giorgetta, her husband Michele, and her young lover Luigi. This simmering love triangle has been there all along, loitering in the heat and the shadows. From here onwards, though, there is no turning back, and the opera becomes a hyperventilated piece of film noir. With only Humphrey Bogart missing in action, Puccini hurtles us along with his distinct dramatic flair and lyrical urgency towards the opera’s catastrophic conclusion, pausing only once along the way for a pair of late night lovers wandering the banks of the river and a bugle call from some distant barracks.

Despite the fact that Puccini uses a large orchestra, the score has been described as one of ‘orchestral chamber-music’, with the orchestral lines ‘drawn as though with pen instead of a brush’. Looking through the score in preparation for making my chamber arrangement for MWO it seemed to me that the combination of instruments I’d previously used for MWO’s L’heure espagnole would stand me in good stead – namely harp, violin, bassoon and piano, with some minor extra percussion. I started work in November 2019 and completed a draft score in February 2020. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic I’ve continued to tinker with the score, and now as I write I am preparing the rather tricky instrumental parts for the musicians. Puccini demanded that the curtain must be raised before the music starts, so that the audience’s first impression is visual. Given that MWO SmallStages has no curtain, the first challenge at least will be met!